Children and adolescents living with HIV in Nigeria face a six- to eight-fold higher risk of developing cervical cancer. That’s why it’s so important they are protected against HPV – the primary cause of cervical cancer.

Living with HIV weakens the immune system, which is why children need two doses of the HPV vaccine, given six months apart, instead of the usual single dose.

It sounds simple, but the main challenge is discretion.

Protect confidentiality from the start

For most vaccination programmes, visibility is an asset. Names, registers, photos, and dashboards are all used to prove coverage and accountability. But for young people living with HIV, visibility can cause harm. That’s why their care must be delivered with discretion.

HIV remains highly stigmatised in Nigeria. Despite major advances in treatment, disclosure can still expose children and their families to long-term stigma, exclusion, or discrimination.

This sensitivity is reflected in how services are organised. HIV care is often delivered through standalone programmes, deliberately separated from primary healthcare to protect confidentiality. These safeguards are essential, but they also make delivery more difficult.

The primary challenge was not just finding the girls, but reaching them without revealing their identities.

Reach those at risk through trusted networks

Instead of doing anything new, protecting affected girls came from counting on existing relationships.

In Oyo State, girls most in need of the HPV vaccine could be identified through local HIV support clubs and clinics, where they already visited regularly. In these spaces, staff had long-standing relationships with caregivers, making them safe places to introduce conversations about HPV.

Some decision-makers did not like the idea of integrating HPV vaccination into existing HIV programmes, due to the risk of children’s HIV status being exposed through greater visibility. The perception was that children living with HIV would be asked questions by peers, due to receiving an additional vaccine that most wouldn’t receive.

But a senior primary health leader in Oyo State leveraged an existing relationship with leadership in the HIV programme, reassuring them that data protection would be a top priority. That turned initial hesitation into cooperation.

Once approval was granted, counsellors and champions running local HIV programmes helped identify and map affected children to nearby primary health facilities offering HPV vaccination.

Provide guidance where trust already exists

Due to the high prominence of stigma around HIV in Nigeria, it was crucial to address false rumours about cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine.

When caregivers attended sessions at the HIV support clinics, health workers outlined the need for HPV vaccines, and addressed any misconceptions they had. Logs tracking false rumours were also filled out, so that health workers could prepare for any misinformation that future caregivers would likely voice.

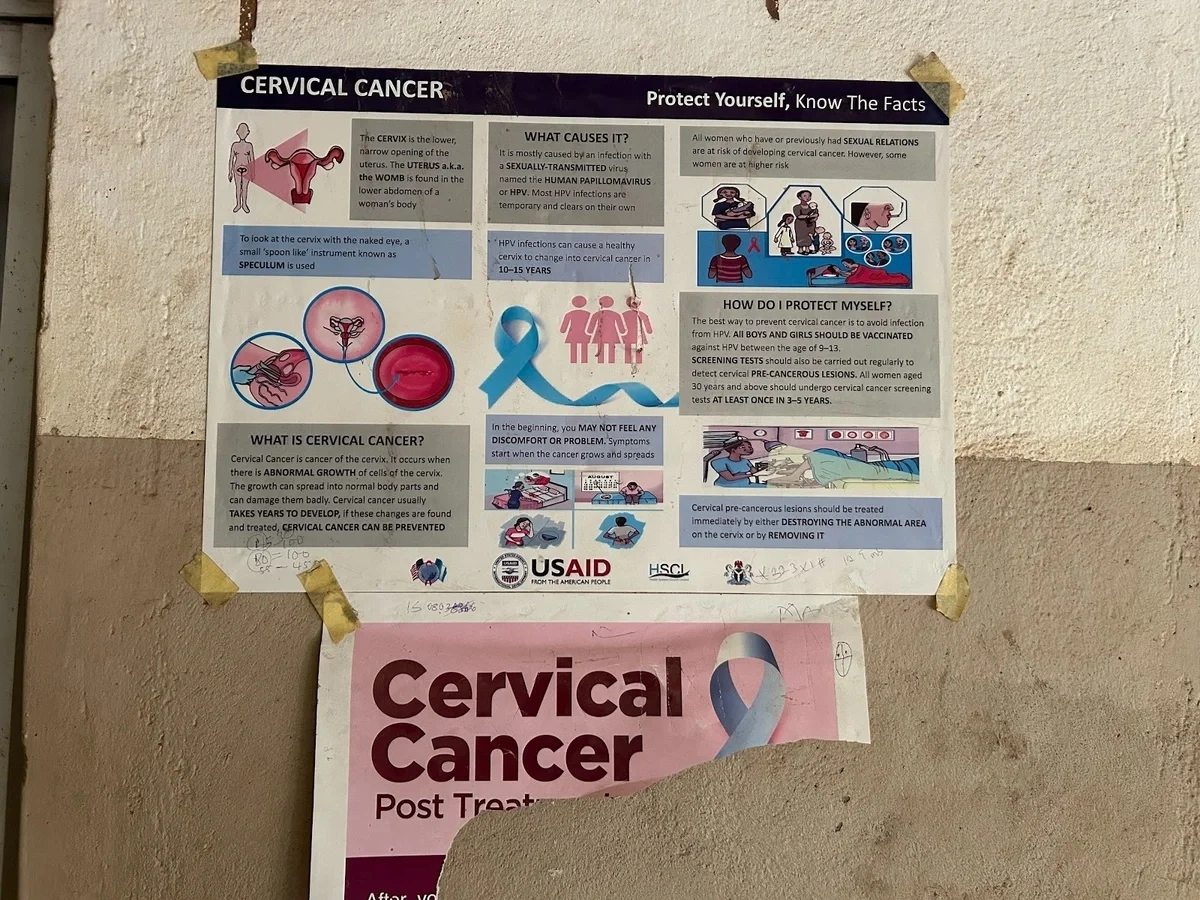

Traditional methods of communication, like radio or television, were avoided, to prevent the potential spread of misinformation, and large visual posters were placed on display in HIV support clinics, to clearly convey the need for HPV vaccines.

A community health worker educating caregivers on the need to vaccinate girls living with HIV against HPV

at a HIV support clinic in Sokoto, Nigeria.

A poster conveying the benefits of taking HPV vaccines at a HIV clinic in Oyo State, Nigeria.

Track missed doses in real time to close gaps

Delivering the first dose was only part of the challenge. National guidance required a second dose six months later, yet existing health information systems had no way of documenting or tracking second-dose HPV vaccinations.

Without a safe way to track follow-up, there was a risk that children would miss their second dose, and progress would be difficult to prove.

To address this, real-time spreadsheet-based tracking tools were used to complement national reporting systems. They were used only by trusted HIV support providers, with key indicators such as age, site, and vaccination date monitored monthly. Follow-ups for second doses were also coordinated through existing HIV services, with trusted community health workers scheduling appointment reminders through phone calls or home visits.

Through this approach, Oyo State fully vaccinated approximately 59% of girls living with HIV against HPV. For a cohort that cannot be publicly mobilised, reaching more than half of the eligible population marked a significant milestone.

Applying learnings in new locations

What began in Oyo State has since informed approaches in other states, including Sokoto, Zamfara and Nasarawa, with discussions underway to extend the model further.

The approach has also been documented in a practical playbook, outlining how HPV vaccination can be delivered through HIV programme platforms without exposing children to harm. This playbook has been shared with national health leadership and discussed with international partners, ensuring the lessons extend beyond a single geography.

To learn more about how we help governments deliver better healthcare for citizens in difficult contexts, read our article about reaching children in security-compromised areas.